Amid a hunger crisis, Houston struggles to keep food on people’s tables - National Geographic |

- Amid a hunger crisis, Houston struggles to keep food on people’s tables - National Geographic

- A History Of Food And Chaos Bonds LA's Salvadoran Community - LAist

- What is the future of work in agri-food? - Brookings Institution

- How to make reindeer food: A simple guide for the Christmas snack - TODAY

- MLGW helps distribute food for Mid-South Food Bank - wreg.com

|

Amid a hunger crisis, Houston struggles to keep food on people’s tables - National Geographic Posted: 11 Dec 2020 07:25 AM PST  |

|

A History Of Food And Chaos Bonds LA's Salvadoran Community - LAist Posted: 11 Dec 2020 07:00 AM PST

Our news is free on LAist. To make sure you get our coverage: Sign up for our daily newsletters. To support our non-profit public service journalism: Donate Now. The connection between food and crisis is one of the open secrets of Salvadoran life, both in Los Angeles and beyond. I've understood this link since I was a curly-haired, pupusa-eating Giants fan who grew up in San Francisco hating the Dodgers and, by extension, all things Los Angeles. That changed in 1991, when I returned from fighting in the war in El Salvador and moved to L.A. where I started working at CARECEN, the largest Central American aid organization in the United States.

CARECEN was, and still is, located in L.A.'s Pico-Union neighborhood, the densely populated area that spawned MS-13 and other maras, Salvadoran gangs whose name originally meant "friends" or "group of friends." The maras came together out of immigrant loneliness, meeting at street corners and parks. As the heavily armed Crips, Bloods and Mexican Mafia pressured them, they adopted the rituals and structure of these larger, more established gangs, which relied on violence for power and profit. While I was at CARECEN, we provided services — legal aid, food programs, health, job training — to refugees fleeing the wars in Guatemala and El Salvador as well as immigrants from Mexico, Honduras and other countries. Between the non-stop crises of daily life in Pico-Union, one of the poorest, most densely populated neighborhoods in Los Angeles, I watched as the end of El Salvador's war and the 1992 riots marked marked the tumultuous birth of a permanent Central American community in L.A.

Before that, the majority of the Salvadorans I knew had planned to return home. For most of them, that never happened. After living here for years, they had found jobs and built families. Their kids, who had been born and raised in the U.S., had no direct connection to their parents' homeland. And after 12 years enduring one of the bloodiest civil wars in the hemisphere, El Salvador's economy was in tatters. As a result, L.A. boasts one of the highest concentrations of Salvadoran restaurants anywhere in the world outside of El Salvador. During those sad years, a period I describe in my recent memoir, Unforgetting: A Memoir of Family, Migration, Gangs, and the Revolution in the Americas, I had, without knowing it, been mixing food and chaos. Regardless of the situation I was navigating — riots, war, genocide, gang violence, govenment violence — my adventures were eased by the comforts of food. One afternoon, early in my time at CARECEN, I met a reluctant donor named Leland beneath the smoky skies of post-riot Pico-Union. I was hoping Leland would give us money to help start a youth job and education program designed to steer teenagers away from gang life:

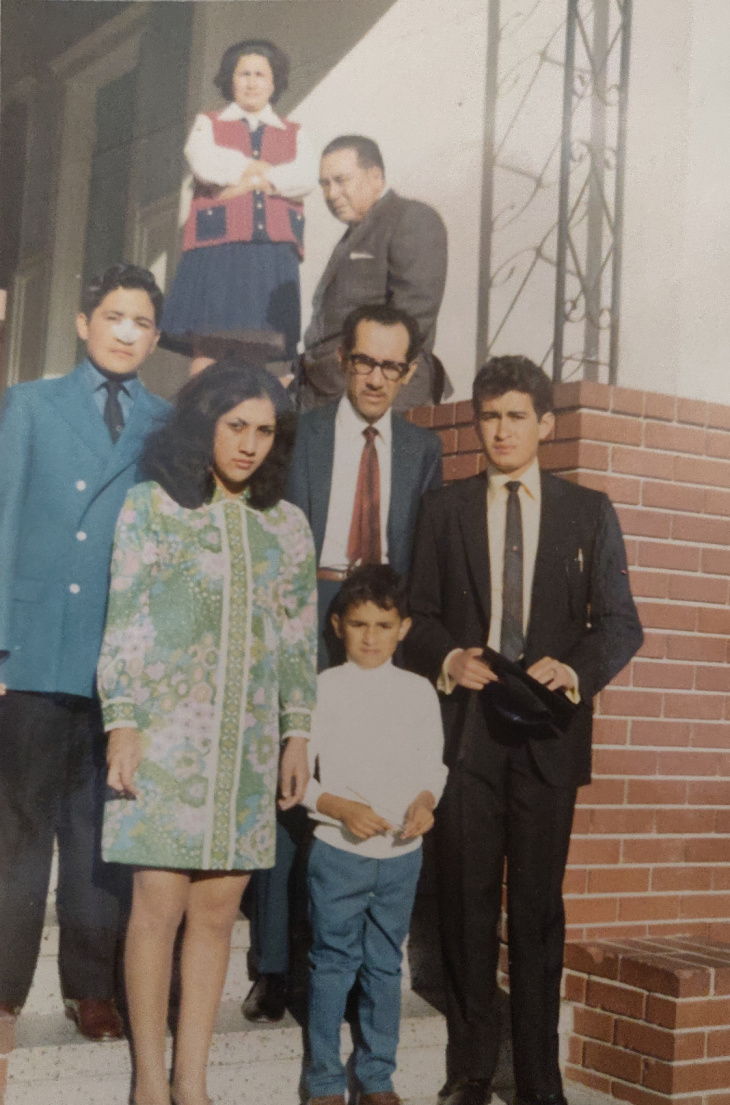

I hadn't thought much about the role food played in my life during those years. It was only when my friend and fellow writer Myriam Gurba described the "warm presence of music, poetry and food" after reading a draft of Unforgetting that I realized how deeply food was woven into the fabric of my book — and my life. In the perpetually crisis-challenged lives of Salvadoran families like mine, food has always been there for us. Although Salvadorans wouldn't start coming to the U.S. en masse until the early 1980s, the dark clouds of war began looming over our lives in the 1970s. As refugees filled my parents' crowded Mission District apartment in San Francisco, they brought news of impending conflict. They also brought panes con chumpe, epic Salvadoran turkey sandwiches that helped us stomach the terror swirling underneath our festive parties:

Once war broke out in El Salvador in 1980, food became a source of solace, especially to those involved in or impacted by the conflict. Salvadoran food was there for me in 2015, when I returned to El Salvador to research my book. Over a typical Salvadoran breakfast, my driver, Isaias, began unspooling stories about his experiences as a member of an elite special forces unit during the civil war:

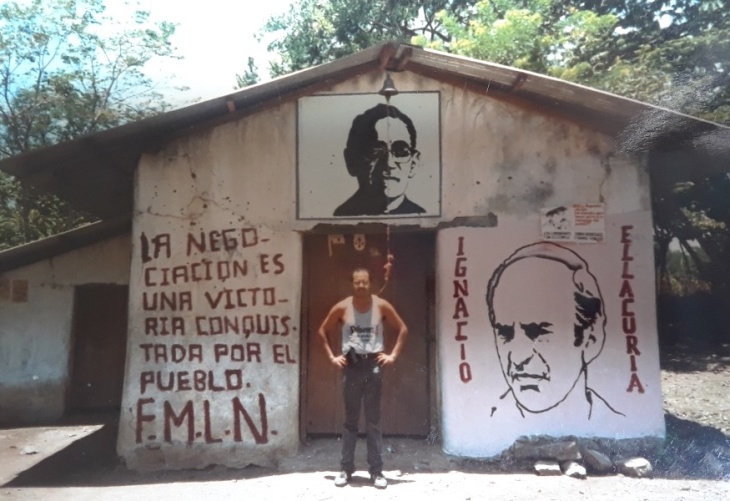

During the strife in El Salvador, Mister Donut's casamiento (black beans fried in butter with white rice), semita (Salvadoran sweet bread) and coffee were often part of the meetings I held in broad daylight with urban commandos of the FMLN guerrillas as we planned to sabotage bridges, energy installations and other military targets. I had returned to El Salvador in 1990, at age 28, to join the fight against the fascist government. Such open meetings — eating in restaurants, in fancy hotels, in neighborhood coffee shops — were a way to hide in plain sight. They helped us avoid the spies working for the military dictatorship ruling the country, a regime that was responsible for slaughtering 85% of the 80,000 people killed during the war, according to an exhaustive report from the United Nations Truth Commission. In 1991, at the tail end of the war, I returned to L.A. where the refugee crisis, fueled by El Salvador's civil war, had transformed the City of Angels. It was now home to the second largest Salvadoran population outside of San Salvador. Most Salvadoreños who came here ended up in Pico-Union, Hollywood, South L.A. or the San Fernando Valley, all of which saw a boom in pupusas, whether at Salvadoran restaurants or on the streets.

Three decades later, many young Central Americans are still dealing with the same ambiguities of language, food and identity that I struggled to reconcile as a child:

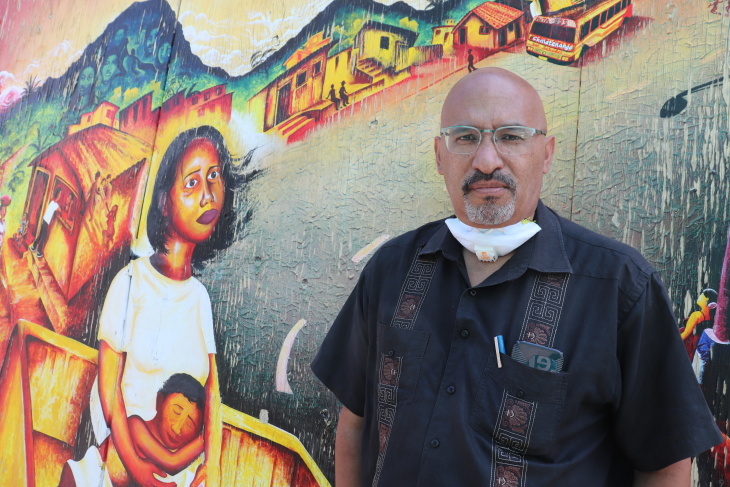

But Salvadorans today have a major advantage: the history and fruits of struggle that are also rooted in the United States. Young Salvadorans in Los Angeles (and around the country) have advantages I lacked. They have academic and cultural institutions to support them, a community to guide them and thousands of Salvadoran restaurants to nourish their bodies and remind them of their origins. During a recent walk around MacArthur Park, the spiritual — and criminal — center of the Pico-Union neighborhood, I looked at the water gushing out of the fountain in the middle of the lake where many guns rest. (Bodies used to rest there too.)

In some ways, the crowded park feels exactly the same. It remains crowded with very poor people, gangs still operate in and around the park and vendors still sell elotes, hot dogs and other things. In other ways, things have profoundly changed. Many of the older Salvadoran restaurants that once ringed the park have either closed or moved, as have many former residents. The schools are newer and, most importantly, Pico-Union is the symbolic rather than the population center of L.A.'s Salvadoran and Central American residents, who have established major communities in South L.A., Van Nuys and other parts of the city. Salvadorans, now tied for the third largest Latino subgroup in the U.S., have faced half a century of riots, extreme poverty, horrific violence and forced migration. But we have also rebounded with courage, intelligence, ferocity and food, all of which helped us not only survive but to put down roots and build community, even as we form part of the larger Los Angeles.

WE LOVE TO ANSWER YOUR QUESTIONS |

|

What is the future of work in agri-food? - Brookings Institution Posted: 11 Dec 2020 06:22 AM PST Up to 80 percent of the labor force in low-income countries works in agri-food, mostly on the farm. In high-income countries, the proportion is still about 10 percent, more than half of them off the farm, in the related food industry and services, and many, migrant workers. Unsurprisingly, much hope is pinned on the agri-food system to tackle the global challenges of good-job creation and poverty reduction. Meanwhile, agricultural automation is advancing rapidly, especially in developed countries; localization of food production is reducing access to external markets for developing countries; and anti-migrant sentiments are flying high. COVID-19 reinforces these trends of digitization and deglobalization. Furthermore, employment in agri-food historically declines as countries develop. So, what will be the role of agri-food in the future of work? Overall, the challenge is to transition to fewer and better paying agri-food jobs—on-farm and increasingly off-farm along the agri-food chains—without causing social havoc and making maximum use of the many employment opportunities agri-food will continue to offer, particularly for youth. This challenge is going to be especially salient in Africa. More and more diverse food with fewer laborersAs countries develop, people spend a smaller share of their income on food and more of it on nutrient-rich, processed, and convenient foods. This transformation is possible as farmers become more productive. Employment in agriculture declines, while new jobs are created off the farm, in the food industry and services, to cater to the changing customer demands (Figure 1). The expansion of off-farm, agri-food jobs partly compensates for the loss of on-farm work. Generated in towns close to poor populations, these off-farm jobs have also been an important factor in reducing poverty. Figure 1. As economies grow, agri-food job creation shifts beyond the farm, while on-farm jobs become fewer and betterSource: Thurlow, 2020, Measuring Agricultural Transformation, presentation at USAID, Washington D.C. 2020 (https://www.slideshare.net/ifpri/aggdp-agemp-measuring-agricultural-transformation) This process takes time. As a result, the agri-food system will remain a major employer for many decades, especially for lower-skilled workers in low and low-middle income countries, even though the trend in agricultural employment is fundamentally downward. Agricultural productivity is a key driver of this structural change. In the developing world during 1960-2000, every half-ton increase in staple yields generated a 14 to 19 percent higher GDP per capita and a 4.6 to 5.6 percent lower labor share in agriculture five years later. Continued investment in public goods is required to make agriculture more productive and help sort its workers into on- and off-farm activities including those in agri-food chains. Digitization and deglobalizationAs the transformation unfolds, societies evolve from having a surplus of domestic farm labor to a shortage. With inelastic food demand, an increase in productivity (a shift in the supply curve) will lead to a significant decline in food prices. Land markets are usually inefficient and food value chain development sluggish. This slows farm consolidation and diversification to higher-value crops, which are necessary for farm incomes to keep up with more secure and faster-growing incomes off the farm. Farming becomes increasingly unattractive for many, and agricultural workers become harder to find. In higher-income countries this emerging farm labor shortage is often filled by foreign agricultural wage workers, especially in difficult-to-automate tasks like harvesting fresh fruits and vegetables. Headlines this spring of a shortage of 1 million seasonal migrant farm workers in Europe following COVID-19 mobility restrictions vividly illustrate this reality. Rising anxiety about the availability of migrant labor coupled with growing anti-migrant sentiments increasingly call this migrant labor model into question. Rapid advances in agricultural robotization, data mining, and sensor technology offer a viable alternative. Robo-weeders, automated strawberry pickers and now also vertical farms are just a few more recent examples of technologies that reduce the demand for labor. They also enable reshoring of agricultural production. Agricultural deglobalization and digitization thus combine to (prematurely) close a door for agricultural labor and poverty reduction in lower-income countries. But agricultural digitization also offers important opportunities to increase labor productivity and raise incomes among many in the developing world. Hello Tractor, an Uber-like platform for tractor services that started in Nigeria, and Twiga Foods, a platform linking smallholder producers with urban consumers in Kenya, are just two examples. The applications are many and increasingly widespread, in agricultural extension, in finance (agri-wallet), in supply chain management (quality control), and in information management. Together they will accelerate the transformation toward fewer and better jobs, on-farm and also off- farm, including in the broader agri-food system. Inclusive value chains, skills, and social insuranceTo maximally exploit the employment opportunities the food system offers while brokering this transition, three policy areas demand attention. First, to raise agricultural labor productivity, we need to tackle several constraints at once. Inclusive value chain development (iVCD), which contractually links smallholder producers with other value chain actors, is increasingly the organizational solution of choice to accomplish this. Buyers can then secure higher volumes of better quality. They need this to access the more remunerative markets or to operate their plants at scale. Producers receive access to credit, agronomic knowledge, and a reduction of production, price, and/or market risk. But many questions and challenges remain, including the role of producer organizations and how to increase the productivity of staple crops for which iVCD is less effective. Second, proactive measures must be taken to maximally benefit from agricultural digitization and tackle deglobalization. Accelerated regional integration in developing countries (such as the Africa Continental Free Trade Area) can help tackle the premature closing of overseas markets (for agricultural workers as well as goods). For new technologies to play their role, massive investment in skill development (including digital skills) must be pursued, commensurate access to infrastructure assured, and the threat of rising market concentration watched. Finally, the global transition to fewer and better paying jobs, on and off the farm, is wrought with inertia and deep societal tensions. Many current farmers and agricultural wage workers will find themselves ill-equipped or too old to move off the farm. This situation often leaves a bifurcated agricultural workforce and a growing rural-urban divide: A minority of better educated, more entrepreneurial, younger farmers does well, while the majority of mainly older farmers struggles to survive. Simultaneous expansion of social security systems to avoid reversion to ineffective protectionist agricultural policies is needed. Decoupling social insurance provision from employment holds promise, with the massive ramp-up of social assistance across the developing world in response to COVID-19 offering a powerful platform to build on. Rising inequality, accelerated deglobalization, and technological backlash risk being the alternative. |

|

How to make reindeer food: A simple guide for the Christmas snack - TODAY Posted: 11 Dec 2020 06:19 AM PST Santa always gets cookies, but what about his trusty reindeer? While a carrot on the plate might have been enough for generations past, social media-obsessed millennial parents have driven a rise in "reindeer food" — usually an oat-based recipe that gets sprinkled on the lawn and comes with a magical poem to get kids extra excited for the arrival of Rudolph and co. What is reindeer food?The origins of this tradition are decidedly recent, but its popularity has exploded in recent years. Artisanal food shops sell reindeer food, Etsy is full of reindeer food bags and tags,and you can even order the snack on Amazon. But this year, as everyone is looking for ways to make a socially distanced Christmas special, reindeer food is especially appealing. Why? Well, reindeer food packets are easier to mail than cookies for family and friends you can't be with physically; it gives kids stuck at home a creative activity that doesn't include a screen; the mixture can be as sweet or healthy as any individual family wants them to be; and it's an activity kids can do with friends and family they can only see outdoors. How to make reindeer foodTo make your own reindeer food, you just need a recipe and then something to store the food in — anything from a zip-top bag to a Mason jar would work. The recipes vary from edible healthy oats and spices to more fanciful glitter concoctions. Since reindeer food is a new tradition, there is no right or wrong way to make it, except to just be sure that, if you're using glitter and sprinkling it outside, it is edible glitter. Because whether or not you believe in Dasher and Dancer, birds and bugs will certainly eat whatever gets sprinkled and it is definitely not in the Christmas spirit to harm wildlife.  Ali Rosen The easiest (and healthiest) recipe for reindeer food is akin to muesli — perfect for actual animals — and whatever you have left over can be eaten by humans with yogurt or milk for a healthy Christmas morning breakfast. Oats are always at the center, and then adding a bit of green with pistachios and red with dried cranberries makes it feel festive. Adding in sliced almonds and sunflower seeds gives a bit of extra crunch, but items like raisins, coconut, chocolate chips, flax seeds or dried fruits would all work great, too. Top it off with some holiday spices like cinnamon, nutmeg and allspice, and you have the perfect treat to eat at home or share with friends and family. Reindeer food poemsTo make your reindeer food into a gift, you can put it into cellophane bags or Mason jars. Print out or draw tags that include an instructional poem explaining the purpose of the reindeer food. There are a lot of variations on the poem, but one that shows up a lot goes as follows: Sprinkle this reindeer food outside tonight, The moonlight will make it sparkle bright. As the reindeer fly and roam, This will guide them to your home. This is the year of all years to create new traditions — so why not sprinkle a little magic (in healthy snack form) into your holiday?  Nathan Congleton / TODAY  Checka Ciammaichelli / Courtesy \ Checka  Nathan Congleton / TODAY |

|

MLGW helps distribute food for Mid-South Food Bank - wreg.com Posted: 11 Dec 2020 12:38 PM PST  MEMPHIS, Tenn. — Hundreds of families received some extra help thanks to Memphis Light, Gas and Water and the Mid-South Food Bank. Early Friday morning, cars were lined up along Raleigh-Lagrange near the Joyce M. Blackmon Training Center. In the parking lot were nearly 50 volunteers from the utility company sorting food for 500 to 600 families in need. "We weren't looking forward to doing a event in December, but the Lord has blessed and we are having warm weather," said Terica Lamb. It wasn't hard to find employees who wanted to take part in the mobile food give away. MLGW workers said it's always special to give back during the holidays, this year more than ever. "We are seeing more and more families that are food insecure. You know, hour loss, hour reduction. We are just privileged to serve the community in this way," said Lamb. MLGW has worked with the food bank before, but nothing like this until 2020. In fact, this is the fourth give away they've organized this year. "This is the spirit of the company. We are always trying to help," said Gaston Moulin. They plan to keep it up as long as they are needed. If you would like to help the Mid-South Food Bank, click here. Suggest a Correction |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "food" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. |

Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

from What to Cook https://ift.tt/2W9zmYW